Why read Middlemarch?

Those that have read and loved Middlemarch are changed by it. It slowly unfolds and unwraps, revealing the pitfalls of self-centredness and the capacity for ordinary lives in ordinary places to be the catalyst for kindness.

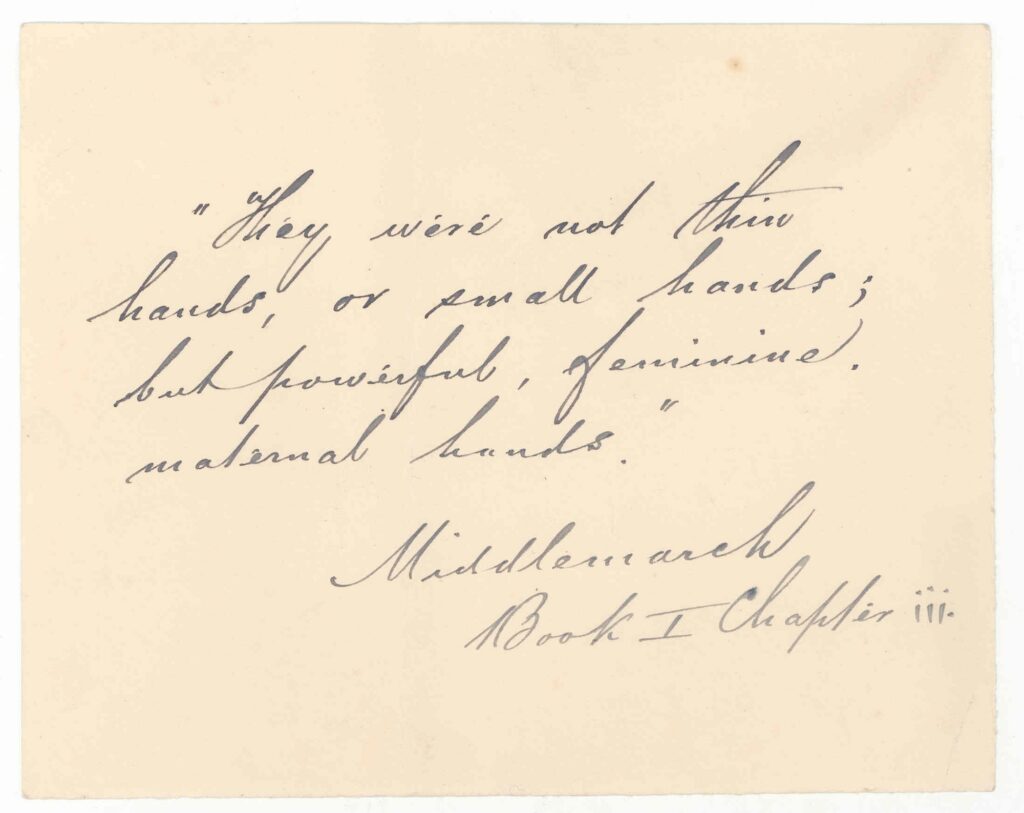

At a little over 900 pages, it is a work of literature that might, on first glance, make the reader feel intimidated. The language too can be complicated; Eliot writes sentences whose effect and meaning reveal themselves over time.

It is daunting when you first hold the novel. But of course the Victorians, when they first read Middlemarch, read it in eight parts from Dec 1871 to Dec 1872. It was easier for them: many weren’t daunted by the size of the text, but rather expectant and excited. Is it possible that 21st century readers, newcomers to Eliot and Middlemarch could be excited too?

Many academics and lovers of literature insist that Middlemarch is as urgent and illuminating as it was when it was first released 150 years ago. How the novel shines a light on our need to better understand each other, showing the dangers of ego and ambition. Lydgate, for example, dreams of identifying the “primitive tissue”, an imagined essential building block of life; Rosamond marries for the purposes of elevating her status in society – but weds herself to something she does not expect. Eliot shows us that greed limits our capacity to make change, and limits our capacity to empathise. Ideas that are pertinent now.

There’s no escaping it: Middlemarch is a colossus, and our modern tendency to consume media quickly – perhaps no more quickly than on social media platforms like Facebook or TikTok, might prevent readers from picking up a copy and opening the first page.

But, there is way. And without labouring this point – Middlemarch has a capacity not only to interest and excite you, but, like all great works of literature, has the capacity to help you see the world and others in a new, sympathetic light. Eliot didn’t write the novel for academics, but for ordinary people. Ordinary people are the heroes and heroines in her story. And she reminds us throughout Middlemarch that there is nothing wrong with that at all: and insists that “the growing good of the world is partly dependent upon unhistoric acts”.

What stops us from reading great literature might just be the sheer act of reading itself. Reading is challenging, and reading for knowledge acquisition (the way we do when we are searching for information on Google) brings about an inattentiveness and an attention deficit. However, there is hope. Books are like dynamos: they require a little spinning before they run on their own. Reading is essentially a convoluted kind of listening: we decode the word on the page, and the words and ideas sound in our heads. If you want to read one of the greatest books in the English literary canon, try listening to the story first. Borrow the audiobook from your library and let George Eliot weave her magic.

Toby Keane is our guest curator for our series on Middlemarch.

He lives in Cornwall, and is a writer, teacher and musician.